Robotic Pancreas: Can millions of diabetics be put on autopilot ?

Jeffrey Brewer was on top of the world. For years he had put in 100-hour workweeks as cofounder of two early Internet juggernauts: local guide Citysearch and the online advertising pioneer GoTo.com (later renamed Overture). But by 2001, with more than enough money to live on for the rest of his life, the 32-year-old handed off control of Overture and set out on a yearlong trip to Australia with his wife and two kids. Upon their return to the States, though, they noticed something odd. Seven-year-old Sean was unquenchably thirsty and urinating far more often than usual. On September 19, 2002, they took him to the pediatrician. The doctor gave him a urine test and announced without hesitation, “Your son has type 1 diabetes.”

Jeffrey Brewer was on top of the world. For years he had put in 100-hour workweeks as cofounder of two early Internet juggernauts: local guide Citysearch and the online advertising pioneer GoTo.com (later renamed Overture). But by 2001, with more than enough money to live on for the rest of his life, the 32-year-old handed off control of Overture and set out on a yearlong trip to Australia with his wife and two kids. Upon their return to the States, though, they noticed something odd. Seven-year-old Sean was unquenchably thirsty and urinating far more often than usual. On September 19, 2002, they took him to the pediatrician. The doctor gave him a urine test and announced without hesitation, “Your son has type 1 diabetes.”

Previously known as juvenile diabetes because it is usually diagnosed before adulthood, type 1 is the “other” kind of diabetes, the kind no amount of dietary adjustment will hold at bay. It develops rapidly, due to a mysterious autoimmune reaction that attacks the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Treatment requires insulin injections and relentless hour-by-hour diet control. Short-term, the main risk is hypoglycemia — low blood-sugar level caused by too much insulin — which makes patients exhausted and confused, leading to unconsciousness and death if not treated immediately with something sweet. But the opposite problem, high blood sugar, raises the long-term risks of kidney failure, blindness, amputation, and heart disease. Either way, type 1 diabetics live on the edge, a cupcake away from a coma.

Nurses taught the Brewers how to inject the insulin and how to prick Sean’s finger for the drop of blood to test his blood-sugar level with a little meter. They learned a simple algorithm: If their son’s blood sugar was this high, give him so many units of insulin; if it was this much higher, give him that much more. It’s a crude scale that every one of the more than 1 million type 1 diabetics in the US makes do with daily.

Tall, thin, and intense, Brewer was shocked by the antiquated approach. “I had this logbook,” he says. “I’m testing Sean every few hours, and I’m thinking, this is crying out for automation. A computer should do this and would do it better. Why didn’t this exist, with all that we can do?”

So began phase II of Brewer’s life. He would become advocate-in-chief for bringing to market a breakthrough technology that has been promised for decades: a fully automated, self-regulating artificial organ — mechanical and electronic rather than biological — that would sense blood-sugar levels continuously and release just the right amount of insulin at just the right time without the need for any action, or even awareness, on the patient’s part. Good-bye to many-times-daily blood tests. Farewell to insulin injections containing back-of-the-napkin dosages and inevitable hours of feeling ill. Good riddance to the risk of slipping into unconsciousness and an untimely death. Brewer would start the race to build a technological fix for diabetes. The biggest obstacle? Bureaucratic logjams.

Everyone, Brewer soon found out, had an excellent reason for not letting Sean and other diabetics fly on autopilot. Manufacturers were afraid of liability, academics were bent on achieving perfection, and the Food and Drug Administration was downright jumpy at the thought of letting a computer control a mechanism with life-and-death responsibilities.

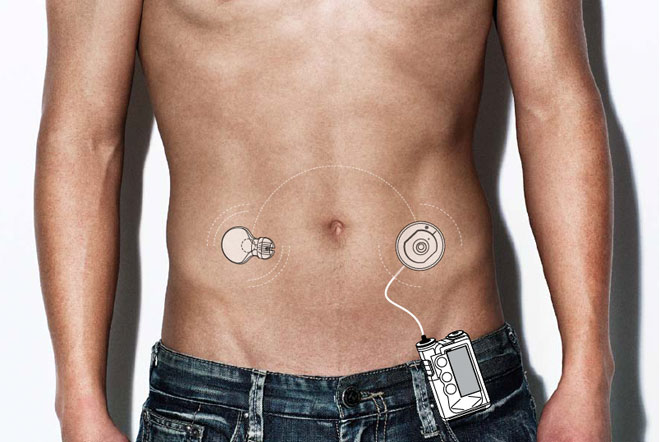

Yet most of the components for what researchers were calling an artificial pancreas — an external device the size of an iPod that would duplicate the insulin-secreting and -regulating functions of that organ — were already in place. An insulin pump had been approved back in the late 1970s, and a continuous glucose monitor that read the output of a sensor implanted under the skin was nearing approval. (The first one would hit the market in 2005.) The trick was to connect the two via software, letting the monitor’s information on blood-sugar levels — high or low, rising or falling — serve as the basis for calculating exactly how much insulin to release.

Brewer flung himself into the challenge with the same passion he had brought to his Internet startups. Less than a month after his son’s diagnosis, at a meeting of the Diabetes Technology Society, he was ready to shake things up. After listening to an arcane academic debate about which algorithm would be best for the pump, Brewer stood up in the audience and began berating the scientists for dithering over details. “We have all the pieces,” he said. “We need to start commercializing these technologies, because people living with the disease need it.”

The audience broke into applause.

Then Brewer hit the road, traveling to the leading manufacturers in diabetes technology. He joined the board of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

“I remember it vividly,” says Aaron Kowalski, the JDRF’s assistant vice president for glucose control research, about the first time he witnessed one of Brewer’s applause-inducing interruptions. “It was amazing. I’ve been to many, many scientific meetings, and I don’t know that I’ve ever seen anything like that happen before.”

Source: wired news

Filed under: Strange news